For generations, north looked fixed on paper and steady in classrooms. The latest geomagnetic updates tell a different story. Magnetic north is still in the Arctic, but it is not lingering near old reference points, and the gap between routine drift and operational risk is thinner for systems that depend on precise headings.

Scientists are not framing this as sudden chaos. They are framing it as an update challenge. As the pole keeps moving and space weather adds short swings, mapping teams, pilots, mariners, and software engineers are being pushed to treat magnetic north as a changing input, not a permanent backdrop.

Scientists Track Two Different North Poles

NOAA separates the magnetic dip pole from the geomagnetic pole, and that distinction changes how movement is read. The dip pole is where field lines point straight down into Earth, while the geomagnetic pole comes from an idealized global dipole fit. Treating them as the same point can blur real motion and hide model uncertainty.

That framework is now central to public data releases, because agencies publish coordinates, not vague arrows. Once north is defined with math and repeatable methods, year-to-year shifts can be tested against observations instead of debated as anecdotes. It improves consistency across navigation software.

The 2025 to 2030 Track Shows A Clear Arctic March

The WMM2025 north dip pole file lists six yearly positions, from 85.762°N, 139.298°E in 2025 to 84.723°N, 126.092°E in 2030. Read together, those points form a coherent path across the high Arctic sector rather than a random wobble around old Canadian-era descriptions. Longitude shifts are steady, and latitude changes are measurable.

That matters because planners work from explicit coordinates for each year in the cycle. A model track with annual waypoints makes it easier to compare forecast and reality, and to spot when inherited assumptions about direction are no longer reliable. The path trends westward in longitude each year.

Speed Is Still High Even As The Pole Eases Slightly

Using the WMM2025 coordinates, annual step distances land in roughly the low-30s to mid-30s kilometers per year, with the first interval near 36 km. NOAA’s December 2025 assessment reports the observed north dip pole speed at about 36 km per year from 2025 to 2026, closely aligned with forecast expectations.

So the story is not a sudden jump beyond physics; it is sustained fast drift in operational terms. When that pace persists over multiple update cycles, small heading assumptions age quickly, especially in high-latitude corridors where magnetic geometry is already demanding. Even modest yearly drift compounds over time.

Why Navigation Errors Grow When Updates Lag

Magnetic headings are converted to true headings through declination corrections. If charts, avionics databases, or software keep an older magnetic reference while the pole keeps moving, the correction drifts out of date. Error then accumulates quietly, one release cycle at a time, until crews or systems carry a larger offset than planners expected.

NOAA describes WMM as a standard reference used across navigation systems, including ships, aircraft, and consumer devices. That broad dependence means model freshness is not a niche concern. It is baseline maintenance for direction-aware infrastructure, operations, and safety planning.

Airports Feel The Shift In Runway Numbering Logic

Runway identifiers are tied to magnetic azimuth rounded to the nearest 10 degrees, so a changing magnetic field eventually pushes some runways across a numbering threshold. FAA guidance states this directly, which is why airports occasionally repaint markings, update signage, and synchronize procedures when local declination moves enough.

Even when day-to-day operations look unchanged, that renumbering work reflects a deeper reality: aviation is anchored to magnetic reference, not a frozen map north. The pole’s motion does not ground fleets, but it does force periodic housekeeping that carries real planning and budget weight.

Polar Blackout Zones Keep Pressure On High Latitudes

WMM documentation defines blackout zones as areas where horizontal magnetic intensity drops below 2000 nT, conditions under which declination values are unreliable and compass performance is degraded. Caution zones span 2000 to 6000 nT, where uncertainty remains elevated. Those boundaries move as dip poles migrate.

In practical terms, polar operations cannot treat magnetic quality as constant from one season to the next. Route design, backup procedures, and update cadence need to reflect where these zones sit now, not where they sat on a legacy map built for a different field state. Seasonal planning now matters even more.

Space Weather Can Add Temporary Heading Shock

NOAA’s 2025 geomagnetic field report notes that strong and severe storms, including one extreme event, produced temporary declination deviations above 15 degrees at high geomagnetic latitudes. Those swings are short-lived, but during active periods they can stretch the gap between model expectation and magnetic behavior.

This is why drift alone is not the full risk picture. Slow core-driven change sets the baseline, while storm-driven disturbances add bursts of error on top. Navigation resilience depends on planning for both, especially where operations already sit near the edge of magnetic reliability during active storm windows.

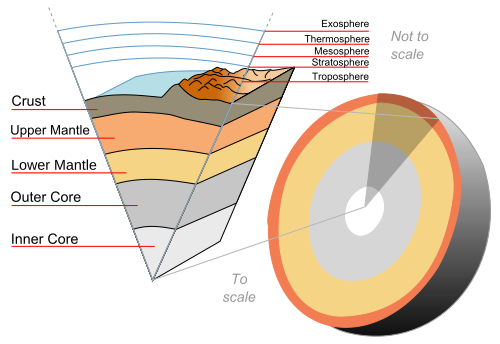

The Engine Sits Deep In Earth’s Outer Core

The main magnetic field is generated by fluid motion in Earth’s outer core, and NOAA describes that system as continuously changing and only partly predictable over long horizons. Surface compasses register that deep motion indirectly, which is why pole drift is best read as a geophysical signal, not a technical glitch.

IGRF-14, finalized in Nov. 2024 by the IAGA task force, provides shared coefficients used across research and operational tools. When those coefficients evolve, modeled pole locations evolve too. The chain from molten iron flow to charted north is abstract in math, but concrete in navigation outcomes.

The Models Are Holding, But They Need Active Care

Recent NOAA assessments show WMM2025 performance remains within specification limits, with root-mean-square errors still controlled and forecast drift tracking observations well. That result is encouraging because it indicates the model is capturing current behavior with useful fidelity rather than drifting out of practical range.

But good performance does not remove workload. It reinforces it. Agencies still need annual checks, software refreshes, and disciplined communication between data teams and operators, because a valid model can still be misused if local systems run stale parameters or delayed update cycles now.

What Specialists Are Quietly Changing Right Now

Navigation planners are tightening update habits, stress-testing high-latitude procedures, and pairing magnetic references with stronger cross-checks from inertial and satellite-based systems. The goal is straightforward: keep magnetic corrections current enough that routine movement does not become an avoidable source of operational friction.

Seen this way, the faster shift is less a dramatic headline and more a systems test. The organizations that perform best are the ones treating geomagnetic change as normal engineering input, with maintenance, ownership, and fewer assumptions that yesterday’s north still fits tomorrow.

Across air routes, shipping lanes, polar science camps, and everyday phones, one quiet truth keeps sharpening: north is alive. The teams that respect that motion, update early, and communicate clearly turn uncertainty into confidence, and they keep movement safer in a world that keeps subtly shifting beneath every compass.