In early Feb. 2026, the sun offered a timely reminder that modern routines depend on forces far beyond Earth’s weather maps. NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center reported that active region AR4366 unleashed repeated major flares, including an X8.1 event, while forecasters also tracked a likely glancing CME influence around Feb. 5-6. People on the surface remained shielded by Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, but communications and navigation systems faced real strain. What appeared as distant solar drama quickly became a practical story about daily technology. Aviation and maritime teams shifted into watch mode.

When A Sunspot Region Refuses To Calm Down

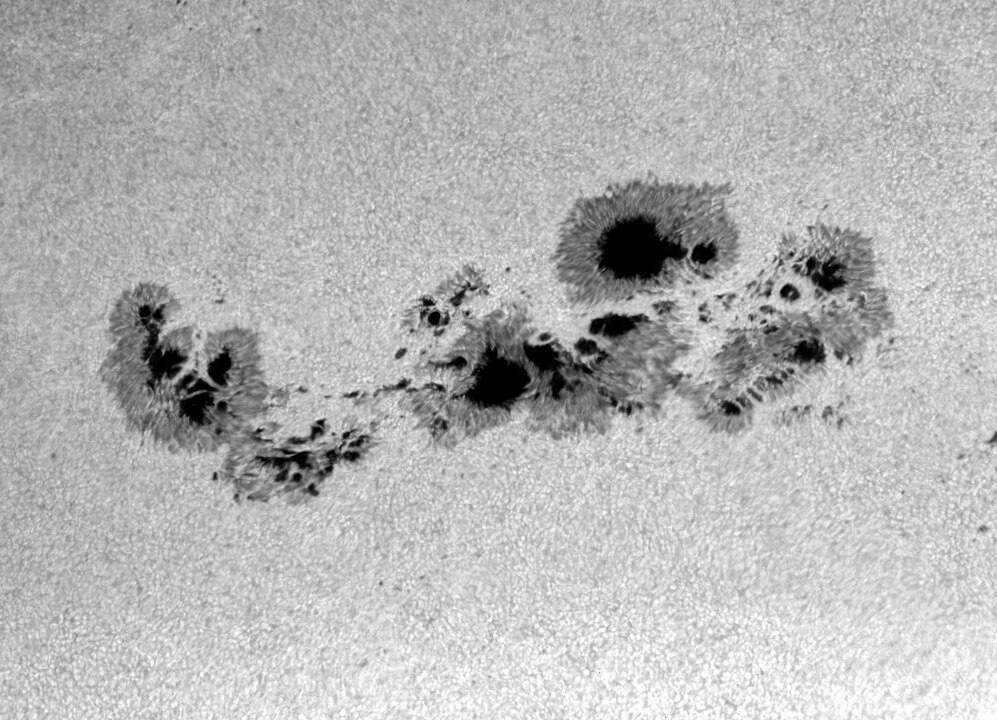

AR4366 did not produce one dramatic burst and then go quiet. NOAA reported a sequence that built over days, with C-class, M-class, and X-class flares stacking from Jan. 30 onward, including an X8.1 flare on Feb. 1 and more strong releases after that. The pattern mattered as much as any single peak.

That cluster behavior is why forecasters stayed on alert instead of treating the episode as a one-time spectacle. Repeated magnetic releases can keep Earth-facing risk elevated, especially when flare activity and CME timing begin to overlap, even when early guidance points to glancing effects first. It became an operational story.

Why Radio Blackouts Hit So Fast

The fastest disruption often arrives before most people hear the term solar storm. During a strong flare, X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation increase ionization in the lower ionosphere, degrading high-frequency radio paths on the sunlit side. That mechanism can interrupt long-distance voice and data traffic in minutes.

NOAA’s R-scale translates this into operations, not theory. At stronger levels, HF contact can be widely lost for about an hour, while low-frequency navigation signals are also degraded, creating pressure for services that rely on stable propagation windows and predictable timing across multiple time zones.

Why The Sunlit Side Feels It First

Dayside geometry decides who feels the communication strain first. NOAA notes that flare-driven radio blackouts are strongest where the sun is overhead, so disruption can concentrate by local time and route location rather than political borders. Aviation and maritime corridors that use HF as a long-haul layer can see conditions shift mid-operation.

That timing effect explains why two regions can report different outcomes from the same solar event. One network may sound normal, while another faces noisy channels, brief dropouts, or rerouting to alternate links as ionospheric conditions change hour by hour within a duty window.

GPS Drift Is A Quiet Disruptor

Navigation usually does not fail in cinematic fashion during space weather. Accuracy erodes first. NOAA explains that disturbed ionospheric plasma bends GPS signals in ways quiet-time models cannot fully correct, so position errors can grow from roughly meter-level performance into tens of meters during severe conditions.

For logistics, precision farming, surveying, and time-sensitive transport, that drift can become expensive fast. In stronger disturbances, receivers may lose lock on satellites, turning a normally invisible atmospheric layer into missed coordinates, delayed dispatches, and cautious operational slowdowns.

Satellites Suffer Signal Noise Before Outages

Satellite users often notice space weather as instability rather than total silence. NOAA describes ionospheric scintillation as interference created when irregular plasma structures refract and diffract signals, producing fading at the receiver. The result can be jittery links, intermittent drops, and degraded throughput on affected paths.

NASA also notes that strong flares can affect satellites and spacecraft beyond Earth’s lower-atmosphere protection. That means operators track both immediate signal quality and hardware exposure, because communication performance and on-orbit system health can degrade on different timelines.

Geomagnetic Currents Pressure Power Infrastructure

Power grids are vulnerable through long grounded conductors, not through dramatic sparks from the sky. NOAA explains that geomagnetic storms can drive geomagnetically induced currents in transmission networks, pushing transformers outside ideal operating ranges and stressing equipment designed for steadier electrical behavior.

Most events remain manageable with preparation, but higher levels can force protective actions and tighter grid operations. The same storms that paint auroras can challenge voltage control and infrastructure reliability, especially across higher-latitude systems where geomagnetic effects are often strongest.

Alerts And Warnings Turn Science Into Action

Space weather response is now practical, coordinated, and public-facing. NOAA issues alerts, watches, and warnings with severity levels tied to expected impacts, giving operators a shared language for decisions across aviation, power, GPS, radio, and satellite sectors. The goal is earlier action while options still exist.

That framework matters in emergencies. When flare sequences intensify, teams can shift frequencies, adjust flight communication plans, harden timing dependencies, and postpone higher-risk tasks. Forecast lead time is never perfect, but structured alerts reduce surprises and shorten recovery after disruptions.

Auroras And Infrastructure Risk Share One Cause

Auroras are beautiful evidence of a disturbed magnetic environment, not a separate show unrelated to infrastructure risk. NOAA links auroral activity with the same geomagnetic dynamics that can disrupt GNSS, influence HF communication, and generate currents in power systems. The lights and the technical strain share one physical engine.

That dual reality changes public understanding of space weather. A vivid sky in higher latitudes may coincide with monitoring by utilities, satellite teams, and forecasters. Wonder and caution can coexist, because the same solar energy that creates spectacle can pressure systems built for stability.

Better Observatories Are Improving Forecast Confidence

Scientists are watching with stronger tools than in earlier cycles, and that is improving preparedness. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory provides near-continuous monitoring of the sun, while ESA’s Solar Orbiter studies how magnetic activity rises, releases, and shapes the space environment around Earth. Better observation does not stop eruptions, but it sharpens forecasts.

NASA and NOAA announced in Oct. 2024 that the sun had entered the solar maximum period of Cycle 25, and NOAA continues monthly cycle updates using sunspot and radio-flux data. That tracking converts solar behavior into operations instead of post-event hindsight.

Prepared Systems Keep Disruption Shorter

The central lesson is neither panic nor complacency. Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field protect human health on the surface from flare radiation, yet modern infrastructure remains exposed enough that strong events can still interrupt ordinary routines. Space weather now belongs in the same planning category as storms, heat, and flooding.

When agencies and operators prepare early, disruptions are shorter and less costly. Utilities and dispatch centers benefit from rehearsed fallback plans. Solar outbursts will continue, but clearer forecasts, shared alerts, and resilient design keep communication and technology services steady.

The recent flare surge did more than light the sky. It revealed how deeply everyday life depends on invisible timing signals and stable networks. When research, forecasting, and practical planning move together, an active sun remains powerful, but far less overwhelming for the systems communities rely on each day.