Earth’s climate has a long memory. Across tens of thousands of years, subtle shifts in sunlight can help ice sheets advance or retreat, cycling between glacials and interglacials. The 2026 question is timing: orbital rhythms still exist, but greenhouse gases are now high enough to overpower the next natural cooling step. Recent modeling suggests the next major glacial build-up is not imminent, and human emissions likely delay it for many millennia. Orbit sets the pace, but carbon sets the threshold for ice to grow. That is why talk of a near-term ice age clashes with today’s warming reality, too.

Ice Age Means More Than One Thing

Scientists use “ice age” in two common ways, and the difference matters for headlines. In the broad sense, Earth is still in an ice age because permanent ice remains at the poles, and the current warmth is an interglacial within that longer cold era. When people worry about an ice age, they usually mean a glacial period, when continental ice sheets expand far beyond the Arctic over thousands of years, sea level falls, and ecosystems reorganize, so mixing the terms turns deep time into drama and makes a slow process sound like something that arrives overnight, as if cities would freeze next decade.

Milankovitch Cycles Set The Long Rhythm

Milankovitch cycles are slow changes in Earth’s orbit and spin that reshape how sunlight is distributed through the seasons. NASA describes three main pieces: eccentricity, obliquity, and precession, which together alter summer sunshine at key latitudes over thousands of years. The ice-sheet story often hinges on northern high latitudes around 65°N, where a slightly cooler summer can let winter snow persist, brightening the surface and amplifying cooling, yet the initial push is small and must repeat for centuries before it shows up clearly in the geological record as a real, sustained trend, too.

The Orbital Signal Works Like A Slow Nudge

Orbital forcing works by stacking small advantages for ice, season after season, until feedbacks take over. If summer sunshine drops enough in the north, less snow melts, surfaces stay brighter, and cooler air can linger, but that build is measured in centuries, not news cycles. That slow pace is why a run of snowy winters, a cold snap, or one dramatic storm does not mean glaciation has begun, and why scientists look for long, regional patterns in summer melt, ocean circulation, greenhouse gases, and ice volume instead of weather headlines, recorded in sediments and ice cores over time, again.

CO2 Acts Like A Gate For Ice Growth

Sunlight sets the background conditions, but CO2 often decides whether ice can actually take hold. A 2016 Nature paper by Ganopolski and colleagues notes that summer insolation is near a minimum today, yet there are no signs of a new glaciation, linking the “missed” inception to relatively high late-Holocene CO2 and low orbital eccentricity. Their simulations describe a critical insolation–CO2 relationship, meaning higher CO2 raises the bar for ice-sheet growth even when the orbital setup looks favorable, so northern summers must be much cooler than they would otherwise need to be to start at all.

Low Eccentricity Favors A Long Interglacial

Earth’s current orbital geometry is unusually gentle compared with times that launched past glacials. Berger and Loutre argued in 2002 that low eccentricity reduces the strength of seasonal sunlight swings, pointing toward an exceptionally long interglacial, sometimes discussed on the order of 50,000 years. With a weaker orbital push, the climate system has a harder time locking into the snow-survives-summer pattern that grows large ice sheets, which helps explain why many projections place any new glacial onset far beyond horizons that matter for people alive now, even without added CO2 today.

Under Natural Conditions, Glaciation Looks Distant

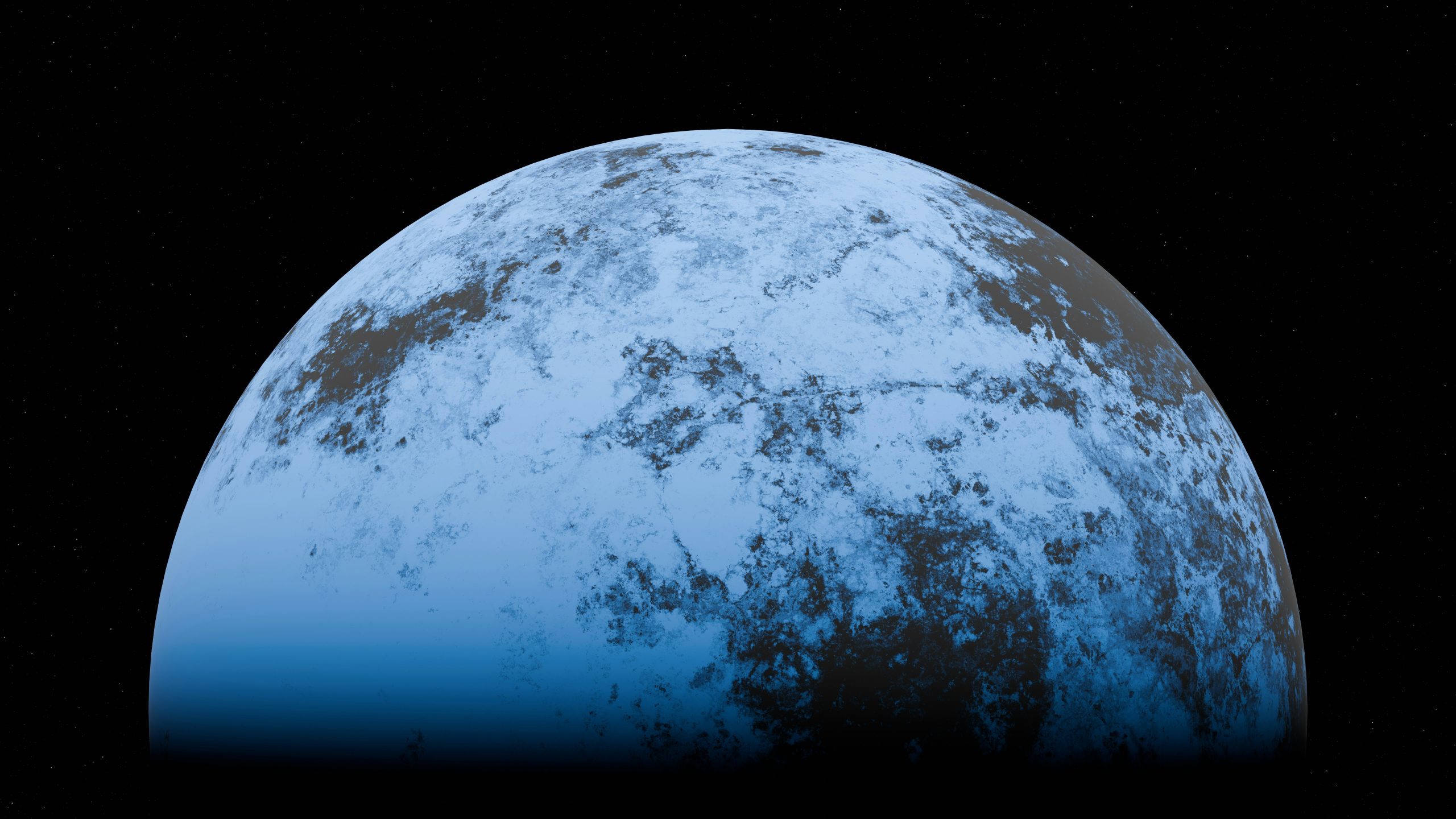

Tonia Kraakman/Unsplash

When climate and ice-sheet models are run without modern human emissions, a common outcome is that the current interglacial lasts a long time. Ganopolski et al. report that, under natural conditions alone, several model versions predict the next glacial inception about 50,000 years from now. They also describe today’s climate as delicately balanced, steering clear of both large-scale Northern Hemisphere glaciation and complete deglaciation, which underscores how far the system is from an obvious tipping point even when orbital forcing is favorable in the near future on human timescales either.