An asteroid alert rarely starts with certainty. It begins with a faint point of light and a short run of observations, so early math can leave room for several futures. When NASA flags a near Earth object as having a possible impact line, the signal is not fate, it is a request for better measurements.

Fresh tracking often tightens the orbit within days, shrinking the uncertainty window until the risky path disappears. Asteroid 2024 YR4 drew attention because early solutions pointed toward Dec. 22, 2032, then follow up data pushed its predicted track safely away. That arc is standard in planetary defense. In plain numbers.

A Flag Is Not A Forecast

Potential trajectory does not mean a countdown. It means Earth still sits inside a wide uncertainty corridor drawn from early sightings, when the orbit is based on a short arc and the future path is still a cloud, not a line.

As new measurements arrive, that corridor narrows fast. NASA and JPL systems such as Sentry publish possible future encounters so telescopes can prioritize follow up and retire false alarms quickly. Most candidates drop off within days or weeks once the orbit tightens and the pass distance becomes clear.

The real signal is transparency: numbers change because uncertainty is shrinking in public view.

The 2024 YR4 Whiplash

Asteroid 2024 YR4 followed a pattern that often confuses people. Early orbit solutions briefly left room for a Dec. 22, 2032 scenario, so it drew attention while analysts asked for more tracking.

Follow up observations tightened the prediction until the concern faded. NASA later stated that updated calculations show no significant threat to Earth in 2032 and beyond, which is the usual direction once the uncertainty window shrinks.

Infrared work also narrowed its size to roughly 53 to 67 m, about 174 to 220 ft, and NASA noted a small 1.7% chance of a lunar impact on that date. The headline shifted, but the method stayed steady.

Why The Odds Move Around

Those early probabilities move because the future path is a bundle of plausible orbits, not a single rail. With limited sightings, small measurement errors widen the corridor and can place Earth inside it for a while.

Each new position report trims the bundle and changes the close approach geometry. Sometimes the risk ticks up before it drops, simply because the corridor is sliding across Earth and then past it. If a close pass sits near a tiny gravitational keyhole, analysts also test how that nudge could shift later encounters.

Frequent updates are not mixed messaging. They are the result of uncertainty collapsing.

What Potentially Hazardous Really Means

Potentially hazardous is a technical filter, not a threat statement. It marks objects that are large enough and pass close enough that they deserve extra attention while their orbits are refined.

NASA’s threshold is based on size and distance, including bodies with a minimum orbit intersection distance of 0.05 au or less and an absolute magnitude of 22.0 or brighter. That sounds abstract, but it is simply a way to rank telescope time and analyst focus.

An object can carry the label and still be forecast to pass safely, like 2005 UK1, which was tracked for a close but safe flyby. The label often reads scarier than the math.

Flybys Happen More Often Than People Think

Near Earth flybys are common, even if only a few make headlines. NASA’s tracking does not focus only on rare, large bodies; it also catalogs smaller rocks that pass safely by, because each new entry reduces unknowns and sharpens the risk picture.

In late Jan. 2026, reports highlighted a bus sized object labeled 2026 AJ among five approaching that day. Estimates put it near 40 ft across with a closest approach near 961,000 miles, outside the Moon’s orbit.

JPL’s Asteroid Watch keeps a Next Five dashboard for passes within 4.6 million miles, listing size estimates and miss distances. Routine monitoring limits surprises.

Distance Sounds Different In Moon Units

Miss distance is easier to grasp when it is anchored to the Moon. The average Earth to Moon distance is about 239,000 miles, so a pass at one million miles is roughly four lunar distances, and it is still within routine tracking.

NASA’s Asteroid Watch window for the Next Five list runs out to 4.6 million miles, about 19.5 lunar distances. That wide net is designed to catch objects worth watching early, before uncertainty has fully collapsed.

Asteroid 2005 UK1 shows the mismatch between label and reality. It is classified as potentially hazardous, yet it was expected to pass safely on Jan. 12, 2026 at more than 32 lunar distances.

Size Drives Consequences More Than Headlines

Size is the quiet detail that changes what a flyby means. Many tracked objects are tens of feet across and may fragment in the atmosphere, while larger bodies can stay intact longer and cause wider disruption.

Early size estimates are often rough because brightness depends on distance and reflectivity, not just diameter. For 2024 YR4, NASA refined the estimate to roughly 53 to 67 m, about 174 to 220 ft, after additional observations.

Planetary defense teams pay closer attention once objects reach the 30 to 50 m range, because that is where a localized impact can become costly. Better sizing turns fear into planning.

How An Alert Travels From Sky To Screen

Behind each alert is a fast pipeline that turns telescope dots into orbits. Observations flow through the Minor Planet Center, then orbit solutions are refined by teams such as JPL’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies as new astrometry arrives.

From there, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office can share status through public tools like Asteroid Watch, Sentry, and the Next Five list. The outputs are simple on purpose: estimated size, miss distance, and closest approach time.

Transparency can feel abrupt because the first numbers are uncertain. Daily updates are not noise, they are uncertainty being reduced in public.

Preparedness Is A Shared Effort

Planetary defense is not a single agency sitting alone with a calculator. It is a network of surveys, observatories, and analysts that share measurements quickly so the orbit can be tested from many angles.

International groups such as the International Asteroid Warning Network coordinate vetted information sharing, while the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group focuses on response planning and mission concepts. Both were created so governments and space agencies can compare notes without delays.

Most alerts end as quiet flybys, but the shared playbook is built for the rare case that does not and the timeline stays tight.

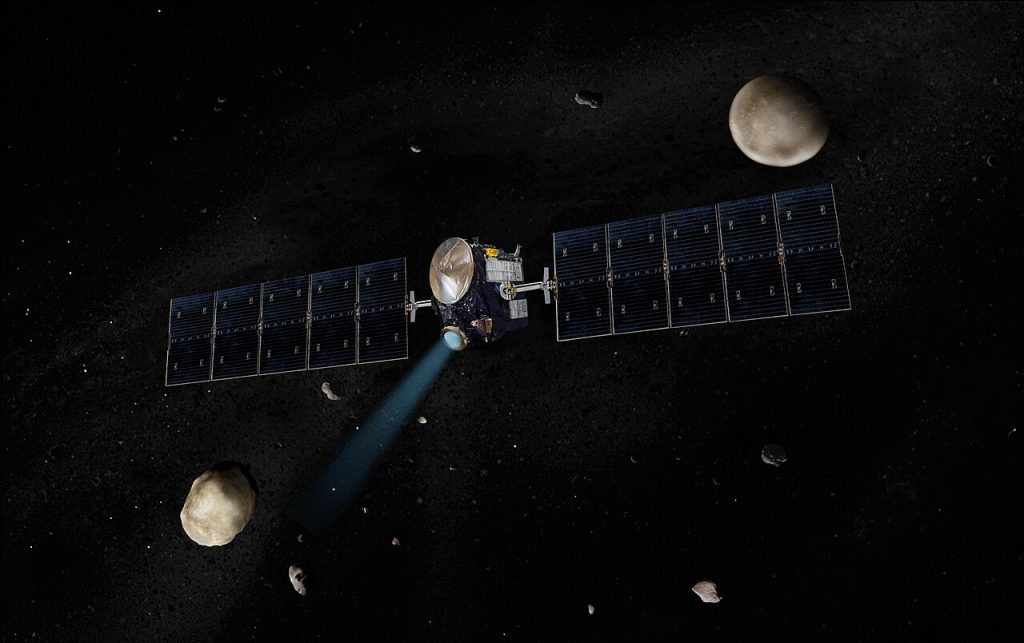

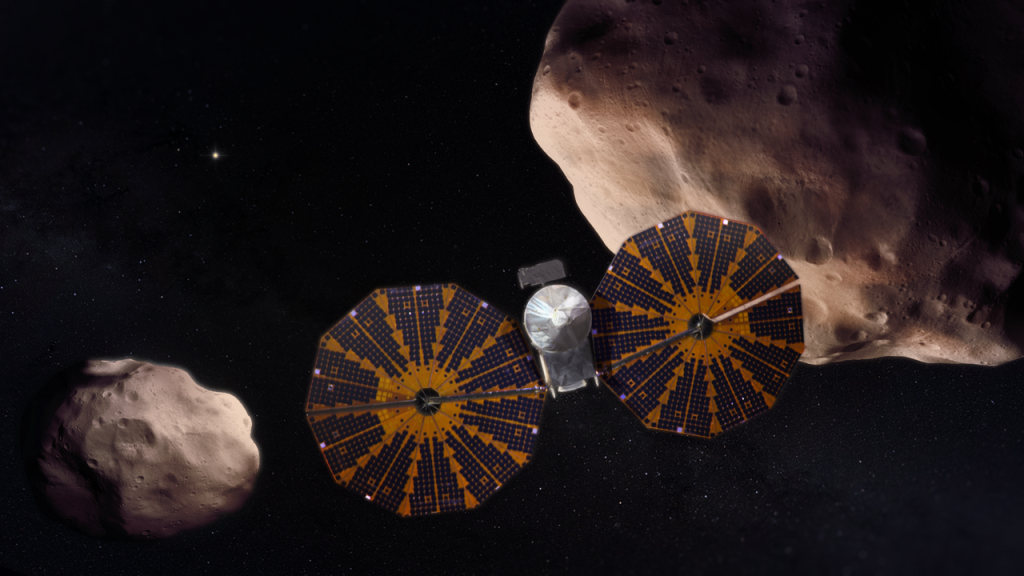

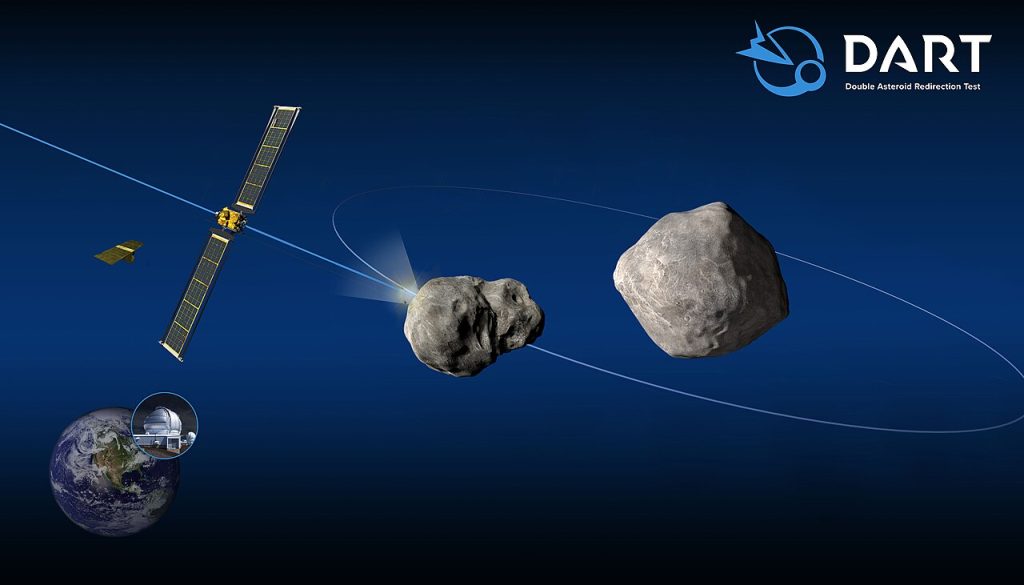

Deflection Is No Longer Just Theory

NASA’s DART mission showed that a controlled nudge can change an asteroid’s motion when there is time to act. On Sept. 26, 2022, DART struck the moonlet Dimorphos, and measurements later confirmed its orbit around Didymos shortened by 32 minutes.

The result did not make Earth safer overnight, but it turned a concept into a measured outcome. It also highlighted the requirement: early discovery, steady tracking, and decisions made with months and years, not days.

That is why fresh alerts matter even when they fade. Each one rehearses the pipeline and supports dedicated discovery missions such as NEO Surveyor. And clear updates.

Most of the time, the story ends with a revised orbit and a safe miss. That outcome is not luck. It is the reward of patient observing, transparent math, and teams that treat uncertainty as a problem to solve in the open. Preparedness grows one update at a time, and it leaves less room for fear to do the talking.