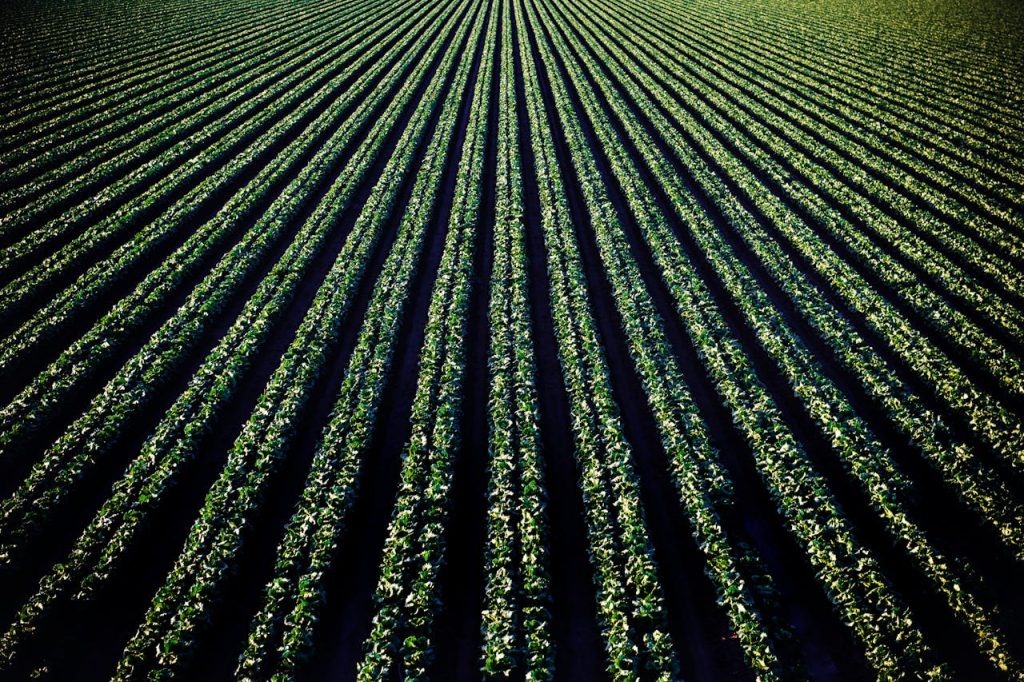

Heat, water scarcity, and tired soils are reshaping what ends up on the plate, and farmers are feeling the pressure first. Across many regions, vegetables still look polished in crates, yet flavor lands flatter once they reach the kitchen. Growers, agronomists, and soil scientists increasingly connect that gap to soil decline: lower organic matter, weaker microbial life, and production systems built for speed over resilience. Regenerative farming is drawing attention because it tries to rebuild soil function and food quality together, while exposing difficult tradeoffs that modern agriculture can no longer ignore across regions.

Soil Decline Shows Up as Flavor Loss

FAO has warned that about one third of soils worldwide are already degraded, and fertility loss does more than trim yield. It also affects food quality, with many fruits and vegetables now less rich in nutrients than they were decades ago, reframing flavor decline as a field signal.

Farmers often describe the same shift in practical terms before any lab result appears: color still looks good, size still sells, but taste complexity fades. When soil biology thins out, crops can mature on schedule while flavor compounds and mineral balance drift in the wrong direction, leaving produce that photographs well yet satisfies less.

Regenerative Farming Starts With Living Soil

Regenerative systems treat soil as active infrastructure, not an inert base for synthetic inputs. Instead of maximizing short-term output alone, growers keep roots in the ground longer, reduce disturbance, rotate crops, and return organic matter to feed microbial cycles that support structure and nutrient flow.

USDA guidance ties these practices to stronger structure and better water movement through the profile. That matters during heat spells, because resilient soil can absorb rainfall, hold moisture longer, and support steadier crop development when irrigation windows shrink and weather swings become harder to predict.

Dry-Farming Changes the Water Math

The Dry Farming Institute defines dry farming as growing through the dry season on moisture stored from the rainy season, with a crop irrigated once or not at all. It is place-based by design, not a universal recipe, and it depends on soils and seasonal patterns that can bank water effectively.

Science reporting from the U.S. West shows why interest is growing: dry-farmed fields can lower irrigation demand while still producing marketable crops where winter rain and suitable soils align. In a water-constrained era, that shift can keep farms viable when allocations tighten and pumping costs move in the wrong direction.

Field Practices Are Precise, Not Romantic

Dry-farming works through disciplined decisions, not luck. Farmers typically plant earlier to capture residual moisture, space plants farther apart, control weeds quickly, and protect the soil surface so evaporation slows through peak heat, especially during long dry intervals.

The Dry Farming Institute highlights the same core playbook: cultivar selection, lower planting density, minimal disturbance, and surface protection. Oregon State extension examples add mulch and low-till routines that conserve water while helping tomatoes and winter squash hold quality through summer stress and uneven wind, when timing mistakes are costly.

Why Flavor Can Improve Under Lower Water

Dry-farmed produce often earns praise for stronger taste, and the mechanism is practical rather than mysterious. When irrigation is reduced in the right context, fruit can develop with less dilution, concentrating sugars, acids, and aromatic compounds that shape depth and persistence.

Peer-reviewed tomato work in California dry-farming systems points to high-quality fruit and better water-use efficiency, while grower experience repeatedly reports flavor gains at market. The same research also notes that variety choice is critical, because genetics strongly shapes both taste and reliability under stress from season to season.

Indigenous Knowledge Predates the Trend

Dryland growing is often marketed as innovation, yet many Indigenous communities have practiced it for generations. In the U.S. Southwest, Hopi farming traditions developed around rainfall limits, seed stewardship, and reciprocal care for land, with methods refined through close seasonal observation.

Science News documented this continuity through Michael Kotutwa Johnson, who describes dry farming as a way of life rooted in observation and reciprocity. That perspective changes the conversation: resilience is not only technical, it is cultural knowledge that survived despite modern systems often overlooking it and labeling it as new.

It Is Not One Size Fits All

Dry-farming and regenerative transitions can fail when copied without local fit. Successful adoption depends on rainfall pattern, soil depth, texture, timing, crop choice, and management capacity across the season, including labor that can execute details at the right moment.

Even strong advocates stress constraints: without enough winter recharge or adequate water-holding soil, crops may struggle early and never recover. The realistic path in many regions is hybrid management, combining soil-building practices with strategic irrigation, then adjusting year by year instead of forcing one rigid model onto every field.

The Hard Truth Is Economic, Too

Flavor and resilience are valuable, but farm budgets still decide what survives. Transition years can demand more labor, closer monitoring, and new routines before soil biology stabilizes enough to reduce risk, and cash flow pressure can rise before benefits become visible.

Research on tomato dry-farming systems notes benefits, but also warns that dependence on a narrow variety set can create vulnerability. Without supportive buyers, fair contracts, and practical policy support, growers carrying transition costs may be pushed back toward high-input methods that feel safer in the short term, even when soils keep deteriorating.

Restoration Changes What Food Can Be

When soil recovery is sustained, growers often report shifts that extend beyond yield charts: better crumb structure, steadier infiltration, fewer extremes after storms, and produce with clearer character. These outcomes build slowly, then reinforce each other across seasons, especially after several years of consistent management.

Regenerative farming does not promise perfection, and dry-farming is only suitable in specific climates. But together they reveal a clear direction for the next decade: treat soil as living capital, match crops to place, and let food quality rise alongside resilience with fewer false tradeoffs.

In seasons defined by uncertainty, the most durable farms are often the ones that slow down enough to rebuild what cannot be bought quickly: living soil. That work asks for patience, local judgment, and steady support from markets and policy, yet it keeps delivering a simple promise. When soil health improves, food regains character, and farming regains room to endure.