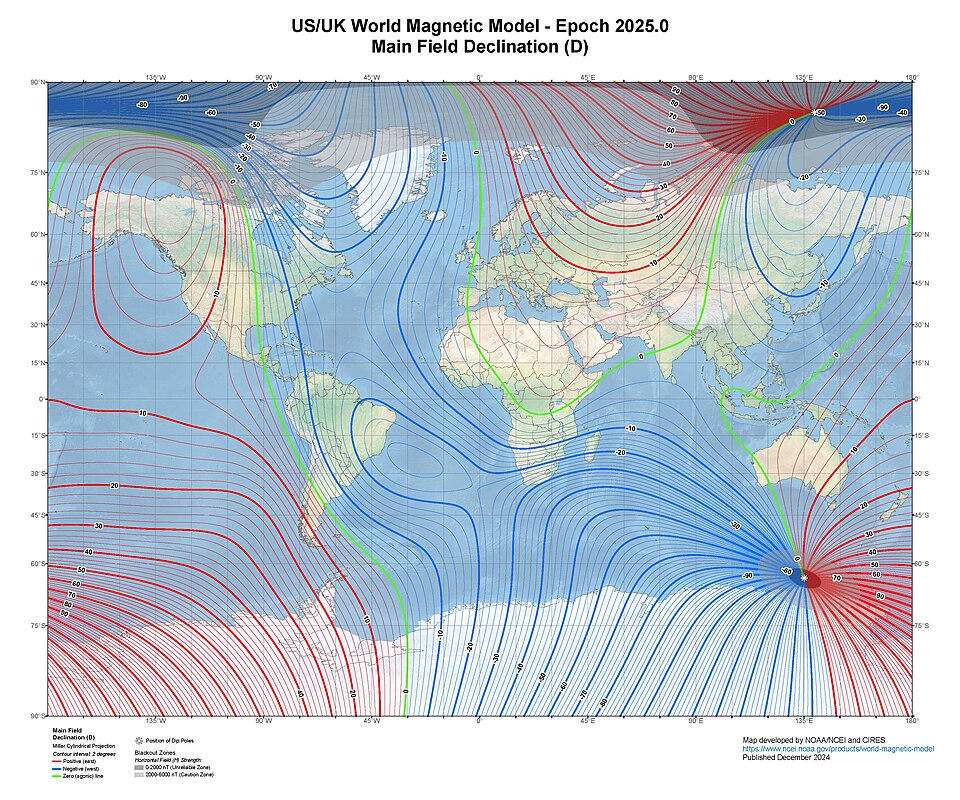

A geomagnetic reversal sounds like science fiction until the rock record says it has happened before. The real tension sits in the messy middle, when Earth’s magnetic shield can weaken and wobble, sometimes dropping as low as 10% of today’s strength. Compasses would misbehave, maps would need updates, and migrating animals could lose their cues. The North Pole has been drifting since 1831, a reminder the field is never perfectly still. For a satellite-and-grid civilization, the bigger worry is a long stretch of harsher space weather, like a global South Atlantic Anomaly, even if the final flip takes many lifetimes.

The Dynamo in the Core Is Powerful but Precarious

Earth’s field is not guaranteed. Mars and Venus lack a similar global shield, while Earth’s core is thought to act like a dynamo. Physics links electricity and magnetism: changing magnetic fields drive currents, and moving electrons generate magnetic fields. Above a solid inner core sits a liquid outer core of iron and nickel, so hot, around 6000°C at its warmest, that it keeps flowing. Convection loops rise, cool, and sink, and the Coriolis effect bends those flows into spirals that help unify the mess into a familiar north-south dipole. It works, but it is also precarious, because the engine is liquid metal in motion.

The North Pole Drift Shows a Field That Never Sits Still

The present field already advertises its restlessness. Since tracking began in 1831, the magnetic North Pole has shifted about 1100 kilometers, leaving its earlier position in Canada and trending toward Siberia. Its pace has also jumped, from roughly 16 kilometers a year to about 55 kilometers a year. That kind of motion can still be a wobble, like a spinning top that leans but stays upright, and it does not prove a reversal is imminent. Still, it explains why compasses can drift off expectations, why mapping agencies must revise reference models, and why animals that key off magnetism might be nudged off course.

The Crust Stores Flip History in Iron-Rich Layers

![Magnetic stripes are the result of reversals of the Earth's field and seafloor spreading. New oceanic crust is magnetized as it forms and then it moves away from the ridge in both directions. The models show a ridge (a) about 5 million years ago (b) about 2 million years ago and (c) in the present.[1]](https://terraplanetearth.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Oceanic.Stripe.Magnetic.Anomalies.Scheme-1024x724.png)

Scientists do not have to guess whether reversals are real. When magma erupts and cools, small amounts of iron within it can rotate while molten, then lock in place as rock solidifies, aligning with the magnetic field at that time. Over time, Earth builds a layered archive. Some layers hold iron pointing one way, and other layers preserve the opposite alignment, implying the entire magnetic polarity flipped. From that evidence, the reference text cites 183 reversals in the last 83 million years. The planet’s compass has rewritten itself many times, even if the calendar of those changes remains hard to predict. Again.

The Schedule Is Lumpy, Even When Averages Look Neat

![Self-made composition of [1], File:Jordens inre-numbers.svg and core from File:PIA00519 Interior of Ganymede.jpg](https://terraplanetearth.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Earth_cutaway.png)

Numbers tempt people into thinking a flip is overdue. The reference text cites an average near 450,000 years between reversals, with recent gaps closer to 300,000 years, and about 750,000 years since the last full reversal. Yet the same record also shows long quiet stretches. One gap during the Cretaceous lasted about 40 million years, and an earlier stretch from 312 to 262 million years ran roughly 50 million years with no reversal. The text suggests mantle and outer-core interplay may disrupt the spiraling flow, but timing still looks stubbornly irregular. About half the time magnetic north returns over geographic south.

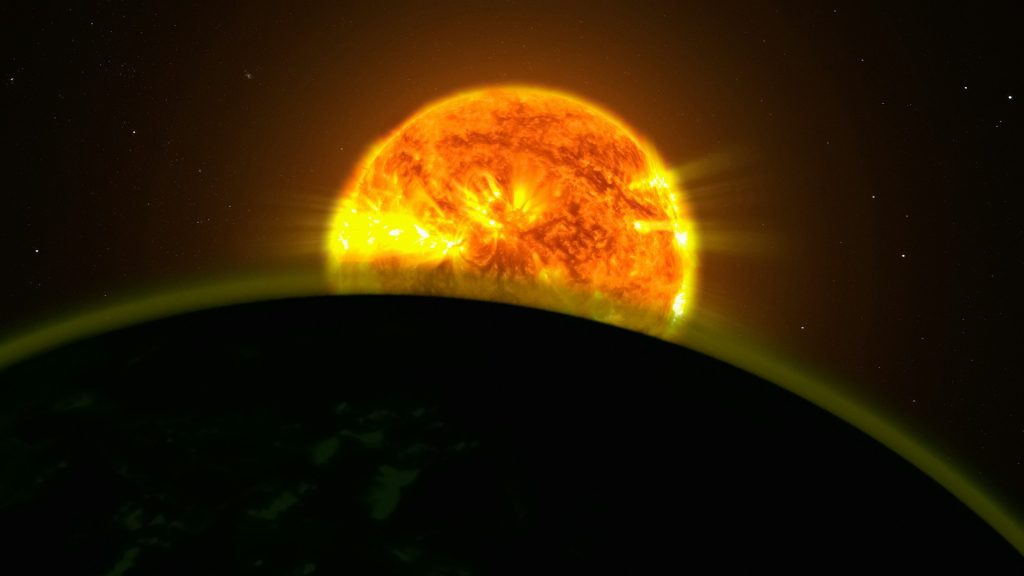

The Danger Window Is the Weakening, Not the Flip

The reference text draws a distinction: the reversal itself is not the main hazard, the buildup is. When the core’s flow loses its neat spiral order, the field can turn chaotic, with several temporary poles appearing. During that interval, overall strength may drop to as low as 10% of today’s level, thinning the shield that deflects solar radiation. Compasses could point the wrong way, maps would need updating, and birds might struggle to navigate. The text describes the return to a stable dipole as taking roughly 1,000 to 10,000 years, long enough to span many lifetimes. A weaker field makes space weather a bigger factor.

Auroras Could Spread While Surface Risks Creep Up

A weaker magnetic shield would not be subtle in the sky. The reference text notes that auroras could reach much farther south during a weakened-field period, because more charged particles would thread into the upper atmosphere. It also flags a human-scale concern: higher radiation exposure could raise skin cancer rates as the field’s deflection power falls. During stronger storms, the difference between a healthy shield and a thin one can decide how much energy gets funneled toward Earth’s near-space environment. The drama would be beautiful, but it would come with a cost that arrives quietly and accumulates. Over time.

Satellites Would Sit on the Front Line of the Change

The reference text paints satellites as early casualties of a weakened field. More radiation can fry circuits, push spacecraft into safe modes, and shorten mission lifetimes, with failures cascading into lost weather data, navigation timing, and communications. It points to the South Atlantic Anomaly as a warning: a region of weakened magnetism around South America that can threaten astronauts and damage satellites. The Hubble Space Telescope, the text notes, has to turn itself off when it passes through. If a reversal-era weakening spread globally, that kind of operational caution could become routine for decades.

Electrical Grids Could Become More Fragile Under Solar Storms

When the magnetic shield thins, the reference text warns that solar storms could bite harder. Electrical grids would be more vulnerable to geomagnetically driven currents, and large regions could face outages that ripple through water, transport, and emergency response. The same period could disrupt satellite communications at the worst moment, leaving fewer backup pathways when coordination matters most. The threat is not constant apocalypse so much as a higher baseline of risk, where a strong storm becomes more damaging because the planet’s protective buffer is weaker. Outages could land as satellite links degrade.