Saltwater crocodiles do not win by speed. They win by making the shoreline do the work, then striking when escape is awkward and help is far. Across northern Australia and Southeast Asia, their hunting can look lazy from a distance, yet it runs on timing, location, and patience that feels almost unfair. They return to the same advantages, notice what repeats, and wait through long quiet hours with only eyes and nostrils exposed. Add tides, glare, and murky water, and the environment becomes a partner that hides the body, narrows options, and amplifies surprise. The setup stays invisible until impact.

They Hunt the Waterline Like a Checklist

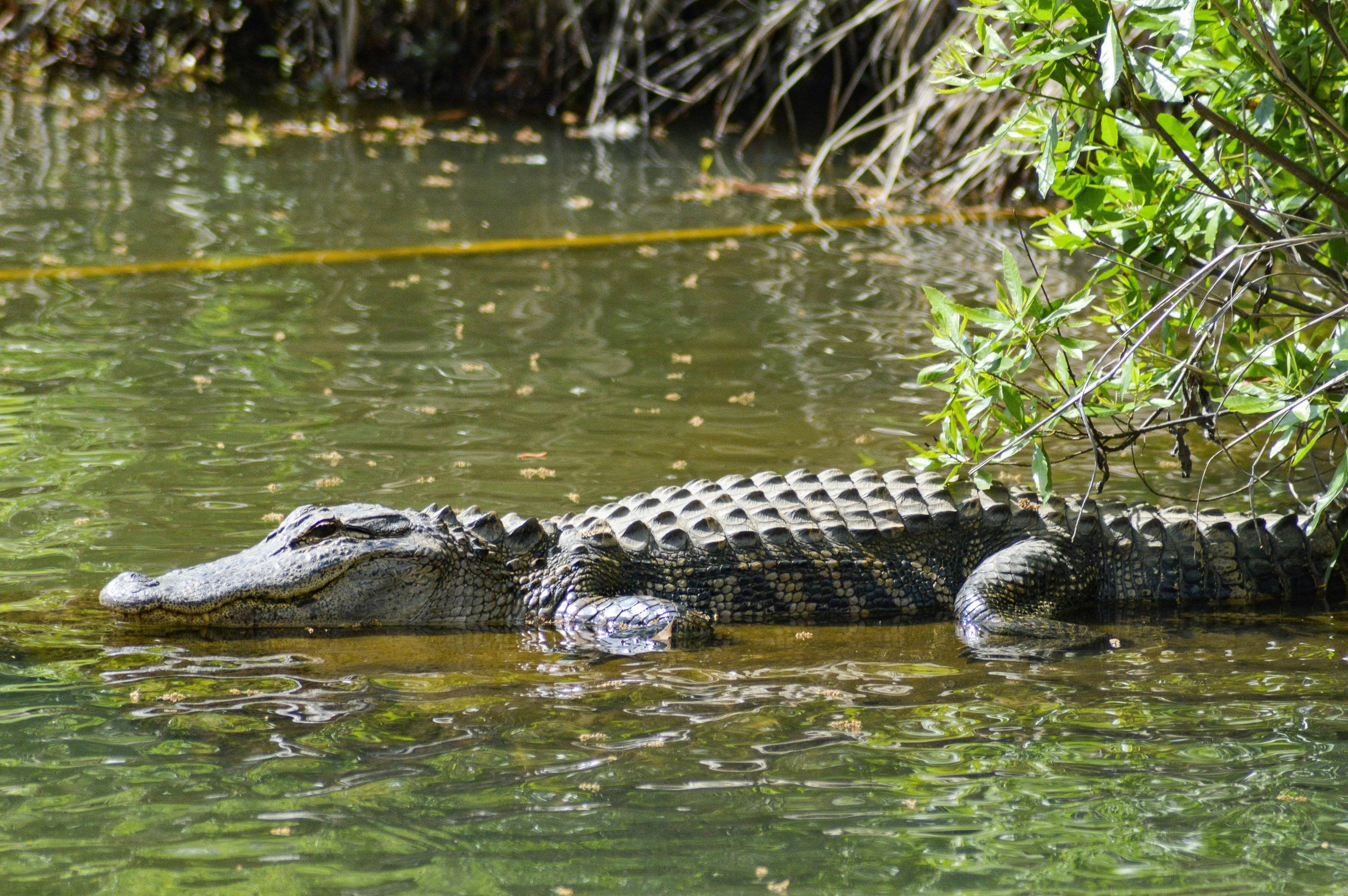

Saltwater crocodiles treat the waterline as prime real estate, because prey must slow down where banks are steep, mud is slick, and hands reach toward the surface for fishing, rinsing, or launching, especially on hot, busy days. In croc country, safety messaging repeats the same point: stay several meters back, avoid crouching, keep children and pets away, and never assume shallow water means safety, because launches can come from the margin. Only a sliver of head may show, yet the body is already lined up for a strike, and the scramble away turns footing, balance, and panic into problems the crocodile planned for.

They Learn Patterns and Revisit Productive Spots

Many predators chase until they are tired, but saltwater crocodiles invest in a place, revisiting productive ramps, bends, and sandbars where routines repeat, weekends blur together, and attention drops. A fishing ledge, livestock crossing, or boat launch becomes a schedule written by others, and guidance warns against returning to the same access point because familiarity trains people to relax at the edge. Over time the croc learns where bodies stand and how long they linger, then waits out the pattern with almost no effort, hunting where behavior is predictable rather than wasting energy hunting everywhere.

They Time Movement With Currents, Not Effort

Long-distance movement is part of the strategy, not a random drift, and tracking studies show estuarine crocodiles timing travel with tide changes and riding surface currents like a conveyor belt over open water. When currents turn against them, they haul out and wait, then ride again, conserving energy while still reaching new river mouths, islands, and mangrove coastlines that look safe to newcomers and tourists. To shoreline watchers it feels like sudden arrival, but it is timing married to ocean physics, letting risk shift far beyond the last sighting and making local memory unreliable for months.

They Can Home Back After Relocation

Relocation sounds like a clean fix until the animal returns, and tracking of translocated saltwater crocodiles has documented strong homing behavior along long coastal routes after release, sometimes over surprising distances. That matters because the map in a crocodile’s head preserves advantage: familiar banks, familiar currents, and familiar choke points where prey is forced to lean, wade, or pause. Managers also note that removing one crocodile can leave a vacancy another fills, so danger may shift rather than end, and a quiet week can still be the calm before a new dominant adult arrives and claims the edge again.

Their Sensory System Reads Water Like a Map

Murky water is not protection against a crocodile, because crocodilians have highly sensitive sensory organs around the jaws that detect tiny water movements and pressure changes with startling accuracy. That system helps explain strikes at night or under glare, since a footstep, a paddling dog, a fish turning, or even a dropped object can broadcast location and timing through vibration. Paired with an ambush posture, the animal can wait for the signal to be perfect, then commit with a precision that feels intentional and almost rehearsed, even though it is biology and repetition doing the work.

They Use Stillness as Camouflage and as Strategy

Stillness is not just camouflage for a saltwater crocodile, it is control, letting the animal hold position for long stretches while staying ready for one explosive surge. Glare, shadow, and floating debris break up the outline, and the lack of motion removes cues that would normally send prey backing away, especially in shallow bends where retreat is messy. Patience also works on human confidence: repeated safe days pull people toward the margin, and by the time the water seems empty, the croc has already chosen angle, depth, and an exit route into cover that hides the body again within seconds.

They Exploit Narrow Channels and Forced Choices

Narrow channels, ramps, and mangrove creeks force choices, and saltwater crocodiles thrive on that geometry when banks are steep, water is deep near the edge, and retreat is clumsy. Currents push bodies and boats into predictable lines while slick mud, roots, and floating logs steal traction, and ordinary tasks like launching, rinsing gear, or freeing a snag keep posture low and hands busy. In these choke points the crocodile is not gambling, it is waiting where options collapse, then striking into confusion it understands better than any visitor who is focused on gear instead of the waterline.

Some Have Been Observed Using Lures

Tool-like tactics are rare enough in reptiles to be unsettling, yet researchers have documented crocodilians balancing twigs or sticks on their snouts during bird nesting season to draw birds closer. Even if it is not widespread, the logic fits saltwater crocodile hunting: minimal movement, maximum payoff, and timing tied to seasonal routines when prey is distracted by building and collecting. A tiny prop can compress distance without revealing intent, which matches the broader pattern of an ambush predator that lets the environment do the persuading, then ends the encounter in one burst at close range.

They Communicate, Guard, and Negotiate Territory

A big saltwater crocodile is a territorial presence that shapes an area for months or years, learning where fish run on a tide, where livestock drink, and where people pause at dusk. Management guidance notes that removing one crocodile can open a vacancy another fills, so the safety picture can change without warning even when the river feels quiet and signs are absent. In good habitat, animals can rotate through the same stretch, and newcomers test banks and ramps that funnel movement. Territory becomes a library of cues, turning one bend of water into repeatable advantage for whichever adult controls it next.

They Turn One Mistake Into a Chain Reaction

Most serious encounters begin with something small, like crouching for a photo, freeing a snag, letting a pet wander, or stepping into shallow water for a quick rinse. Attention is divided and posture is low, so escape is slower and the edge is closer, and these slips cluster at dusk, at ramps, and near dogs that splash and pull forward, with phones out and lines in hand. The crocodile does not need constant success, only one mistake in a place it already controls, and when the strike comes it is less a chase than a trap closing before anyone can stand up, find traction, and react with room to spare.